I spend a lot of time considering corporate storytelling — and why companies commission corporate histories. After all, history and culture books for business form one of the major threads of our business at ECHO Storytelling Agency. Many of those reasons are easy to understand: clients want to celebrate accomplishments like growth, acquisition, and milestone anniversaries; to define their corporate culture for new and existing employees; to stake and defend their territory; and to share their values with external customers, shareholders and suppliers.

One factor that only recently occurred to me is that they aren’t ready to disappear.

Much has been written about the phenomenon known as digital amnesia. It’s commonly argued that the life of a web page currently is 100 days. After that, the content may be altered or the page itself deleted. Sometimes whole sites disappear as smaller companies are bought by larger companies that are themselves bought by Google or, well, maybe just Google. Another study put that same slide to obsolescence, the so-called “rate of decay,” at just 75 days.

Think about that: communication has moved from an oral practice meant to survive generations, to a written one meant to survive centuries, to a digital one that too often survives mere weeks.

I experienced this decay firsthand last year when an online repository of my professional writing was revamped. The designers, brought in to modernize the site and make it both ad- and mobile-friendly, clearly weren’t readers: they deleted the entire archives. All my writing — all everyone’s writing in this magazine library — just gone, a decade’s worth of stories composted to make server room for new blog posts and video snippets. Families, politicians, business titans, doctors, inventors, entertainers — all their stories unmade, all their accomplishments forgotten.

Think about that: communication has moved from an oral practice meant to survive generations, to a written one meant to survive centuries, to a digital one that too often survives mere weeks.

Arguably, it’s my own fault. I trusted that archives, once made, would stand forever. I’m sure cardholders at the Library of Alexandria also felt more than a little upset when they showed up to find the place had burned down. I bear some of the responsibility: I could have made my own website (ugh, the work!) or posted more of my work on my LinkedIn. Cheryl McKinnon, an analyst with Forrester Research, commiserates:

“So much of our communication and content consumption now — whether as individuals, as citizens, as employees — is online and in digital form. We rely on publishers (whether entertainment, corporate, scientific, political) that have moved to predominantly, if not exclusively, digital formats. Once gone or removed from online access we incur black holes in our [online] memory.”

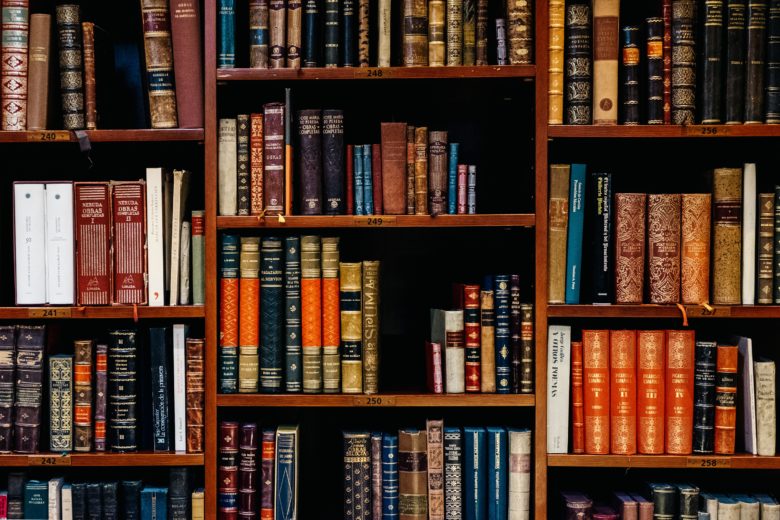

The Long View

At ECHO, we make a lot of books, but we also make digital content. I don’t mean to suggest books = perfect, internet = terrible. Far from it. But a book, from commission to delivery, takes two years to make. That’s a lot of time for reflection and strategy. The internet moves more quickly, and careless mistakes are its norm. We labour hard here to avoid mistakes, but the very medium of digital publishing accommodates — no, celebrates — impermanence. The internet dwells, as a New Yorker article argued last year, in a “never-ending present. It is — elementally — ethereal, ephemeral, unstable, and unreliable.” The piece went on to define “link rot” (when page links lead no longer to the page but to a kind of 404 “missing persons” notice) and “content drift,” which is:

more pernicious than an error message, because it’s impossible to tell that what you’re seeing isn’t what you went to look for: the overwriting, erasure, or moving of the original is invisible. For the law and for the courts, link rot and content drift, which are collectively known as ‘reference rot,’ have been disastrous.…A 2013 survey of law- and policy-related publications found that, at the end of six years, nearly fifty per cent of the URLs cited in those publications no longer worked.”

The piece concludes that building on online research is “like trying to stand on quicksand.”

I don’t mean to suggest books = perfect, internet = terrible. Far from it. But a book, from commission to delivery, takes two years to make. That’s a lot of time for reflection and strategy. The internet moves more quickly, and careless mistakes are its norm.

We do corporate storytelling work for lawyers here, and engineers, and accountants, and other professions for whom reference rot is a central danger. But the real cost of digital amnesia exists for all our clients. Almost all our business partners are well over a decade old. Some are 50; a few, 100. They know where they came from and they treasure their archives. The prospect of losing all that learning and accomplishment understandably alarms them. One overzealous or inexperienced web designer is all it takes to unroot a firm nurtured over decades — which is why I’m so delighted still to work in the world of books. Books are unapologetically old-fashioned. (Let’s leave discussion of ebooks and their utility for another time.) They don’t record “page views” and “unique visits.” They aren’t built for native advertising. “Rich” content in a book means pictures and maybe the odd infographic. And their rate of decay is defined only by how acid-free the paper is, and how much direct sunlight and steamy baths they encounter.

Analog books are as much forever as we have in a digital world. How wonderful.

What’s Next

There are many online resources committed to combatting reference rot. Many are housed at the wonderful Internet Archives. Go there and read deeply.

Vint Cerf, who helped birth the internet in the 1970s, now works as vice president and Chief Internet Evangelist for Google. I’d be keeping an eye on his research. In the same New Yorker article, he talked about the need for long-term online storage, or “digital vellum” as termed it. “I worry that the twenty-first century will become an informational black hole,” he said.

If you have 50 minutes, watch the lovely and informative documentary Digital Amnesia, directed by Bregtje van der Haak and produced by VPRO Backlight.

And if you work for — or own — a company whose accomplishments deserve remembering, you should probably call me.